The next Windsor form in chronological order by date in the Dietrich American Foundation collection is a Philadelphia high-back Windsor armchair that H. Richard Dietrich Jr (1938-2007) acquired from the antiquarian dealer Charles Woolsey Lyon of Millbrook, New York at the beginning of his collecting career. In 1963, Woolsey advertised the armchair in The Magazine Antiques stating, it had been “acquired from a direct descendent of Robert Kennedy Wurts, Esq, who inherited it from his ancestor, one of the foremost original Swedish families to settle in the lower Delaware River area.”

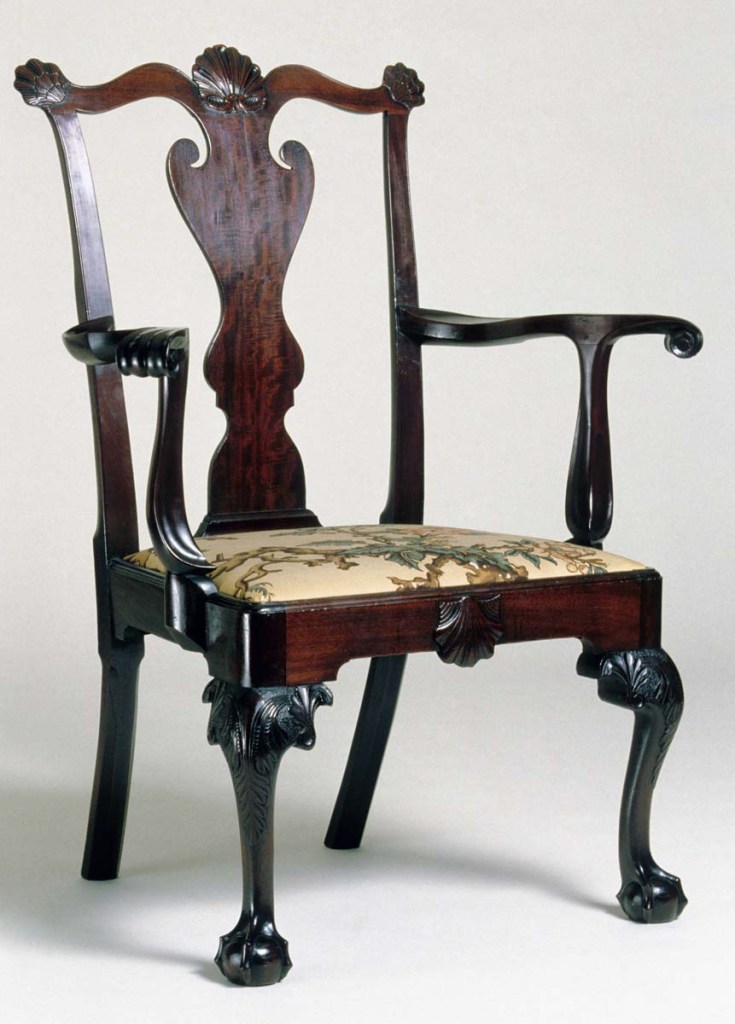

The armchair is distinctive and atypical in several respects. First it is larger than the standard Philadelphia D-seat, high-back Windsor armchair. The width of the seat is 27 inches as opposed to typical D-seat armchairs whose seat widths fall into a narrow range of 23 to 24 ½ inches. The depth of the single-board seat is 20 ½ inches, 3 inches deeper than the 17-inch seat depth of the majority of D-seat Windsors made in Philadelphia. (The seat height and overall heigh of the armchair is within the range of contemporary Philadelphia high-back Windsors.) Because of the greater seat depth, the maker added turned rings to the side stretchers to minimize their length, replicating the long medial stretcher which now has a single bulbous swell instead of the earlier tripartite turning, a design development that roughly coincided with the evolution of legs ending in a tapered cylinder with the elimination of ball feet.

Secondly, the arms, arm supports, and the spindles behind the arm supports are made of mahogany. The handholds are deeply carved, and decorative beads are worked on the top surface of the arms.

Other points of note are the arm supports being placed at a great distance from the front of the seat, and the three-piece arm, derived from high-style corner chairs and adapted for early Philadelphia low-back Windsors. The three-piece arm construction would continue to be an option for oval and shield seat high-back chairs and sack-back Windsor armchairs.

A possibly unique chair at Winterthur is the only Philadelphia Windsor chair larger in scale than the D.A.F. chair. The width of the seat is 34 1/2 inches, the seat depth is 25 1/4 inches, and the overall height is 46 1/4 inches. Evans writes its monumental size “suggests that it could have served a ceremonial function…” Splats similar to those of high style framed chairs are common on English Windsor chairs but this is the only known eighteenth-century American Windsor with this feature.

Both of these chairs are clearly custom ordered but for what purpose remains a mystery. Was the D.A.F. chair made “for a large, if not obese, individual” as Santore suggests or did it serve a a ceremonial purpose as Evans proposes the chair at Winterthur did? The use of mahogany for the arms, arm supports and short spindles on the D.A.F. chair along with the well executed carving of the crest and arms would perhaps argue for the aspirational and experimental aspect of the chair. Were independent carvers and joiners, along with a chairmaker, involved in the production of a complicated object such as this?

The two authors dating of the chairs is confusing. Santore’s date is an attempt to relate the D.A.F. chair to bill in the Carpenters’ Company records dated January 1773 “to cash paid for chares (sic) for the Hall 20s (each.)” A surviving chair at the Carpenters’ Company Hall in Philadelphia shares some similarities of the turned elements on the D.A.F. chair but there are different interpretations of who made which chairs and when at the Carpenters’ Company. Evans’ date for the chair implies she may think that the Winterthur chair was made before the Carpenters’ Company chair, perhaps due to her interpretation of the straight cylinder legs seen on Winterthur’s chair preceded the move to tapered cylinder legs of the Carpenters’ Company chair.

Another discrepancy concerns the wood species of the arms of these chairs. I have examined the arms and arm supports of the D.A.F. chair – they are mahogany and have not been painted. Santore says the arms of the Winterthur chair are mahogany but microanalysis was done on the Winterthur chair and no mahogany is listed in Evans’ book or the current online entry for the chair. Santore asserts the arms of the so-called Speaker’s chairs at the Carpenters’ Company are mahogany but the chairs need to be closely examined to be certain this is accurate.

What is certain, is that new developments in high-back Windsor armchairs were rapidly occurring in Philadelphia in the late 1760s. The popularity of the form drew more chairmakers to take up the production of Windsors. The relationship between Windsor chairmakers who came from a turned-chair background, and cabinetmakers and high-style chairmakers who seem to have begun coordinating with Windsor chairmakers, introducing carved volutes, carved handholds, mahogany and walnut wood species, and even carved shells in the case of one set of high-back Windsor armchairs, is fascinating but little understood due to the scant records of the makers who were involved in producing these compelling objects. William Savery was a turned rush-seat chairmaker who built a business that ultimately included documented high-style framed chairs and cabinetwork. Philadelphia Windsor chairs surviving from the decade preceding the Revolution show us that other chairmakers and joiners in the close-knit, but loosely organized woodworking trades in Philadelphia collaborated to produce these engrossing and intriguing objects.

Chris

Thanks for these observations.

In researching provenance, the papers of Robert Kennedy Wurts’s brother Charles Stewart Wurts III are at HSP and may be worth a look. The family wed into various old Philadephia families. Papers of prior generations are included.

http://findingaid.winterthur.org/html/col544.html

Jay

Correction: the Wurts papers are at Winterthur.

Thanks for this Jay. Apparently R. K. Wurts owned at least one piece of furniture in Hornor’s Blue Book but the piece was credited incorrectly. I don’t hold much hope that the armchair can be traced backwards to an original owner but it’s worth a try. More likely the armchair was collected along the way, hence no prior owners listed on the label. I haven’t begun any genealogical research yet.

First steps are getting accurate wood species ID for the arms on the Winterthur and Carpenters’ Company chairs.

And Peter Strickland has a connection. I don’t think I knew he was going to call 926 Spruce Street The Wurts House!

Chris,

Yes, decorative arts historian Peter Strickland was very much involved. He was the driving force in restoring Wurts House, at 926 Spruce Street, as an historic house museum.

His wife Alice was a Wurts descendant. All of the furnishings collected for it were 19th century, appropriate to the era when the house was built. Peter was expert in that period.

Perhaps Peter’s greatest achievement was that the Wurts House restoration led to the revival of “Portico Row” as a fashionable residential block of single-family houses and condos. Hitherto, it had devolved into a series of derelict houses divvied up into tiny apartments.

The reason I am so familiar with Wurts House is that Peter invited to serve on its board. My mother was also involved, supporting acquisition of some of its furnishings, memorably a Pabst drawings cabinet that had previously stood in the reading room of the Rittenhouse Club.

Sadly, there was insufficient breadth of support to keep the property going as a house museum. I recall the Pabst cabinet and other furnishings from the house ending up at Freeman’s.

Perhaps, it was due to Peter’s involvement that the Wurts papers ended up at Winterthur.

You might also check the articles that Peter wrote. I recall at least one for The Magazine Antiques.

Jay

And Bob Trent also I presume, who was involved with Peter’s work on the house, had a hand in the papers coming to Winterthur?

I believe the Pabst cabinet may be returning to Freeman’s in an upcoming “Decorator Sale.”