A chest-on-chest that will sell on January 21, 2021 at Sotheby’s has been attributed to the Philadelphia cabinetmaker John Folwell (w. 1762-1780) based on the large conjoined initials “JF” inscribed on the top board of the lower case.

The chest may very well be a product of the Folwell shop. Sotheby’s calls Folwell “a little-discussed Philadelphia Cabinetmaker” but he has been often discussed here. It is true though that he is not accorded much space in the traditional story of American furniture history. William Macpherson Hornor, Jr. did seek to promote him as one of the more important cabinetmakers working in Philadelphia in the years leading up to the Revolution, even anointing him the “Thomas Chippendale of America”.

But the objects that have been documented to Folwell are outliers and not domestic products for the home, each is institutional in scope and a one-off – the case housing David Rittenhouse’s Orrery, the Speaker’s chair made for the Pennsylvania State House, and the pulpit of Christ Church. The Speaker’s chair and the Christ Church pulpit remain in the place they were made for, the Orrery has been owned by the University of Pennsylvania since it was purchased from Rittenhouse, though located at various Penn buildings. Hornor attributed no domestic furniture forms to Folwell and neither has anyone else to this day. Folwell’s star faded after his appearance in Hornor’s Blue Book. (The case housing the Rittenhouse Orrery is documented to Folwell and his partner at the time, Parnell Gibbs. They also built a second case for a similar Orrery Rittenhouse sold to Princeton University. That case does not survive, and we do not know how similar it might have been to Penn’s Orrery case.)

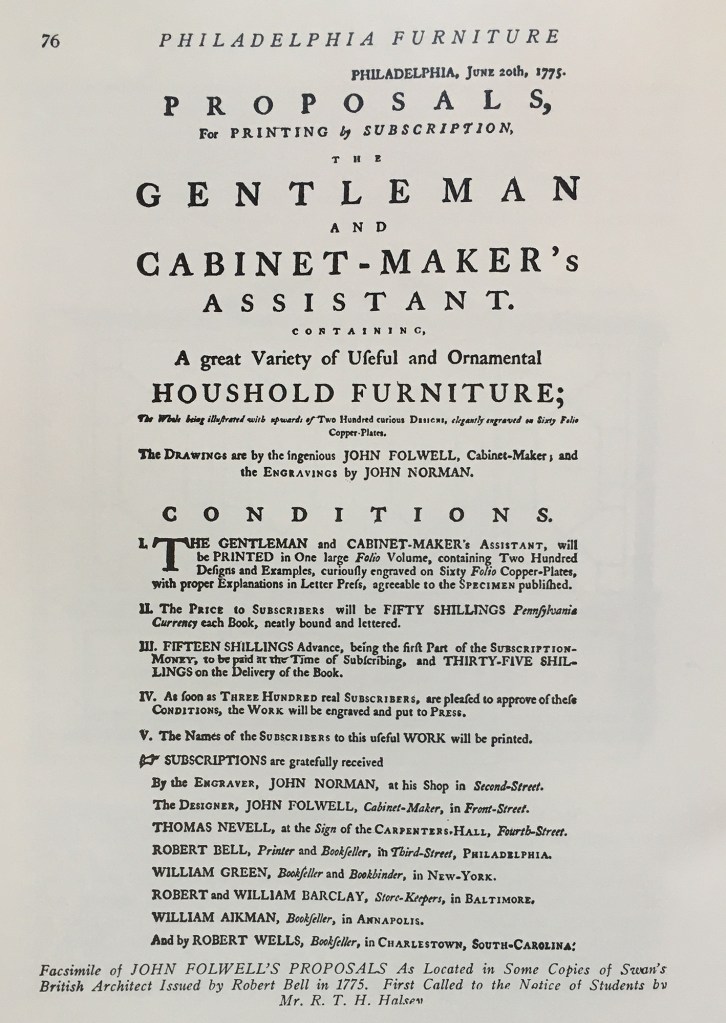

In 1775 Folwell was taking subscriptions for a publication he intended to produce, “The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Assistant”, for which he would do the drawings. No copies of this publication exist, it is thought the coming Revolution put a halt to any attempt at production. Had Folwell’s drawings been engraved by John Norman and the volume been issued as intended, Folwell might have found his rightful place in furniture history.

It’s easy to take pot shots at auction catalogue entries but I know they are often rush jobs written by those starting out in the field, but there are some confusing moments in the entry for there chest-on-chest. There is no construction description, so it is unclear what “a few veneer patches, including a three-inch triangular patch to the top left corner of the second drawer from the bottom” means. Are the drawer fronts veneered? This sometimes occurs on mid-18th century Philadelphia furniture with ovolo moulded drawer fronts, but it is rare. I don’t agree that the “its original masterfully carved basket-and-flowers cartouche” is as masterful as any number of other cartouches from this period. I have not examined the chest in person, but in the photos, I can see several repaired breaks and what appear to be later additions – these are notoriously fragile carvings. In the middle of the entry, it is stated that “it is conclusive that John Folwell was the maker of this chest-on-chest.” Why then does the heading for the chest read “attributed to John Folwell”? There are many such inconsistencies and undocumented statements throughout the entry including the assertion that “the exceptional basket-and-flower cartouche and the foliate carved rosettes displayed on this chest are hallmarks of the work of the celebrated immigrant carver, James Reynolds (c. 1736-1794).” The entry does have footnotes, but there isn’t one for this claim. Is this the opinion of the Sotheby’s employee? Of course, the caveat emptor decree included in all auction catalogues allows for any exaggerated claims we might disagree with.

Ultimately, I am excited to find a form that we might consider to be an example of Folwell’s domestic furniture output. I wish Sotheby’s had shown us an image of the entire board so we could see the placement of the initials, or even give us their height. It is so difficult at this time to examine objects in person that more information on this important object in the history of Philadelphia furniture making is an obligation. I would like to be able to compare it with another chest-on-chest in the Dietrich American Foundation I surveyed for the Foundation.

The chests have some striking similarities, particularly the design and execution of the cornice, but also some differences, the mid-mouldings are handled differently. The backs and sides of the drawers of the Foundation’s chest are sweetgum, what species is used for these elements in the chest at Sotheby’s? Someday we hope to have the opportunity to examine this chest-on-chest that never left the Delaware River Valley where it was made until the recent day it was sent to Sotheby’s in New York.

Chris, thanks for starting a discussion on John Folwell.

Independence National Historical Park has photographs comparing Folwell’s “Speaker’s Chair” at Independence Hall to “The Oriental Chair” owned by the Masons’ Hope Lodge No. 4, Laurel, Delaware, described here: http://www.mastermason.com/Hope-Lodge-Number-Four/hope_4.htm. The lodge was chartered in 1806. Jim Kilvington, I believe, has looked at the Lodge’s chair.

Also, circa 2009, I met Phil Zimmerman at St. Peter’s Church, in Society Hill, Philadelphia, in conjunction with a study he was doing of Folwell’s seating furniture. He pointed out particulars of the chair used by its ministers that were consistent with the carving and construction of the Speaker’s Chair.

All of the chairs cited above were for ceremonial use. Like you, I know of no furniture for domestic use attributed to Folwell apart from the chest-on-chest.

Jay

Jay, thanks for the info on Mason chair in Delaware. I’d be very interested in seeing good images of it. Laurel, Delaware is quite a haul from here, don’t think I will be seeing it in person any time soon.

My wife and I went down to Laurel a few weeks ago specifically to take pictures of the chair.

Any opinion on whether it’s 18th or 19th century?

How often does one find sweet gum used in Philadelphia furniture? I do not get the opportunity to see a lot of period Philadelphia furniture and I just acquired a small chest of drawers that has sweet gum drawer sides and backs. (wood is identified by sight only). Thank you.

Peter,

In The Cabinetmaker’s Account (APS 2019), I discuss the use of gumwood in Philadelphia furniture, at pages 35, 119-121, and 130, and illustrate a dressing table attributed to the shop of Philadelphia joiner John Head (figure 17.17), the corner blocks to which were identified (by Chris, I believe) as sweetgum.

The 1708 probate inventory of Philadelphia joiner Charles Plumley lists “7 Sett Gum bedstead pillars.” In 1756, cabinetmaker John Elliott billed merchant Charles Norris for a “Gum” bedstead. Ibid., at 130, n. 16.

Chris has also written about gumwood as a common secondary wood in this region, in May 25, 2017 and November 12, 2017 posts to this blog, cited in my book. Ibid., at 130, n. 17.

Jay

Thank you.

This previous post from 2017 discusses Sweetgum used in the Delaware River Valley furniture from the late 17th through the 18th centuries.

https://cstorb.com/2017/05/25/secondary-wood-species-part-2/

Its occurrence is relatively rare, but as it’s often misidentified as the commonly used yellow poplar, the true extent of its use has not been appreciated. Interestingly, I have not come across it used as a primary wood in this region as it so frequently was in North Jersey and New York.

Interesting post/chest by Chris, as usual, It’s on the sale block later today and I notice it has 3 pre-sale bids and is presently at 55k, passing its reserve. It will be going home with someone today.

Odd how it is “attributed & conclusively built” in the same listing when it has a makers mark, probably the result of lawyers contributions in addition to other catalog failings Chris mentions.

Not as much important furniture this year in this sale or the sale at Christie’s as in years past but, this carved box attributed to Thomas Dennis caught my eye as well as the estimate of 15-30k, most likely a tease as I predict this box will go for big numbers later today.

https://www.christies.com/lot/lot-a-carved-and-painted-oak-box-attributed-6303445/?from=salesummary&intObjectID=6303445&lid=1

It is said to be a maker’s mark by Sotheby’s. We should leave room for different interpretations of the mark though. It is two initials, not a full name. Owners marked their furniture about as frequently as makers did in the first half of the eighteenth century. And there is no date. Makers frequently, but definitely not universally, added a date of production when signing an object. I don’t know of an instance that an owner dating an object. Owners typically marked objects with a writing implement – pencil, chalk, ink – or used a stamp or branding iron made by a blacksmith. Owners marks are placed in accessible places. Through the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, moving companies sometimes wrote an owner’s name or name and address on the back or top of an object.

Something I don’t, however, associate with an owners mark are skillfully carved large letters such as the “J (or I?) F” as seen on this chest. As I wrote, we don’t have a measurement of the initials, but at any size, this inscription is technically extremely accomplished. Something we could imagine Folwell, a practiced woodworker and a designer who was set to produce drawings meant to rival Thomas Chippendale’s and who was chosen to design the flag for the Light Horse Troop of Philadelphia in 1774, could execute. Interestingly, the Light Horse Troop’s flag that Folwell designed has a conjoined initial cipher above the central design. It is also in an inaccessible location when the chest is set-up and functioning in an owner’s house. It really does seem to have been made by someone proficient in drawing and skilled with a knife or carving tools. Folwell is a documented cabinetmaker working at the time this chest was made. The evidence isn’t conclusive, but I would like to think it is Folwell’s mark.

Chris