William Beakes’ drawer construction is common to late seventeenth and early eighteenth joiner’s work. The wood species were similarly used by the majority of Delaware River Valley joiners and cabinetmakers. Black walnut was the principle primary wood species used in furniture making in the early eighteenth century, drawer sides were most often of hard pine, and the drawer bottoms are made of riven Atlantic white cedar. These two secondary woods were logged in New Jersey, black walnut was primarily logged in Pennsylvania.

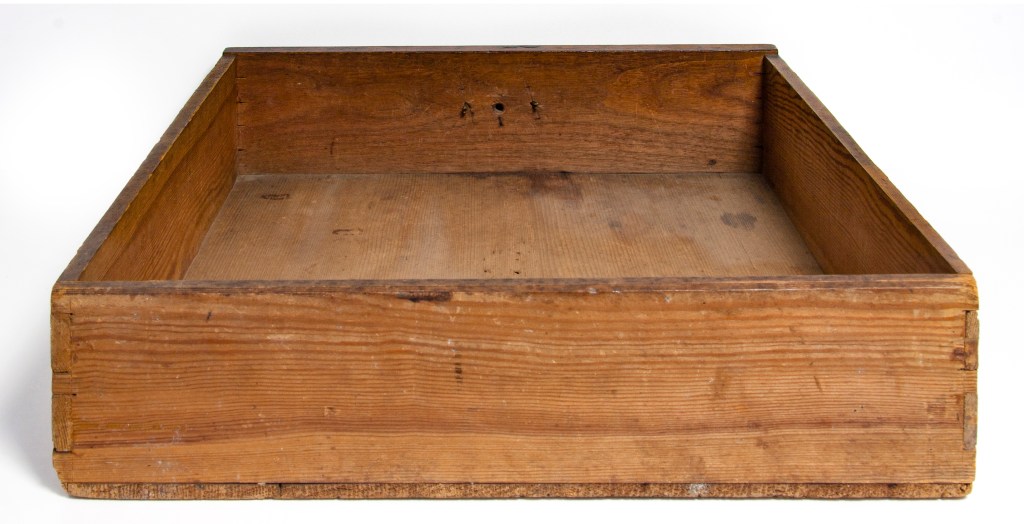

On all the drawers of Beakes’ chests, a flush bottom board is nailed to a rebate in the drawer front and to the bottoms of the sides and back. The top of the drawer sides and back are flat and sit flush or slightly below the front. There is a chamfer on the rear edge of the back.

Was Beakes learn this technique form the joiner he apprenticed with, William Till, or did he adopt it after his time with Till ended? Currently, there is no furniture documented or attributed to Till so the that question cannot be answered at this time. Other unidentified joiners working in Philadelphia and the Delaware River Valley making English furniture forms for the Quaker community before and after Beakes time also used wedges in their dovetail joints.

Many German immigrant furniture makers in Pennsylvania and elsewhere plainly used wedges in their dovetail joinery, but the technique is surely more universal and is to hand for any woodworker, regardless of nationality.

Chris

Thanks.

Here is a useful article on the flora of West Jersey, which includes mention of black walnut:

Click to access The%20Musconetcong%20Valley%20of%20New%20Jersey.pdf

Given the access to Pennsylvania via the Delaware River, it may have been easier and cheaper for furniture makers in West Jersey to obtain their black walnut from Pennsylvania.

Great work!

The only time I have observed wedged dovetails in English/Irish casework was a repair to tighten a (presumably, shrunken) pine drawer side in a lapped drawer front.

An interesting feature of these drawers is the chamfered top rear arrises of the drawers’ back boards, as opposed to a slightly lowered back board with chamfered upper rear corners of the side boards. Is this German influence too?

Thank you. And thanks for your insight into wedged dovetail joints in English/Irish work. In America, it is generally accepted that wedged dovetails have never been observed in furniture made in New England. I also believed this to be true, I had never come across any, and I had been looking. But I recently found a chest documented to a known Boston maker that used wedged dovetails in the upper carcase. I intend the next post to be a brief intro to dovetail wedging, though it is a larger story than I can reasonably do in a blog post. And we don’t have all the answers, if we ever will.

The chamfered top on drawer backs is commonly found in furniture made in the Delaware River Valley. I haven’t thought of it as a German influence, there is so little furniture documented to German immigrant joiners pre-1730 in the Philadelphia area. I’m also not sure that wedging dovetails was necessarily a German influence.