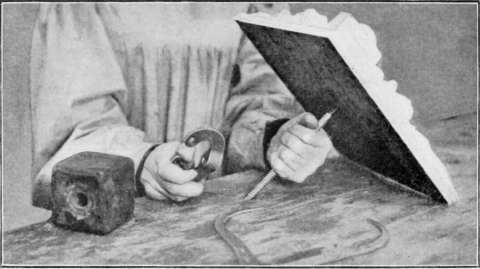

One of my carver’s screws, here attached to a jig, the wing nut or “fly” and a wood spacer. The screw drops into holes drilled in the bench top.

I use carver’s screws with most carving projects. I need to hold a carving securely while retaining the option to work on it from various angles. For centuries, the carver’s screw has been essential for work that requires modeling and that cannot otherwise be conveniently held by clamps or nails. In the photo above, the screw is inserted into a jig for holding drawer fronts to be carved. The square hole in the nut, or fly, fits over the square end of the screw so the screw can be tightened into your carving or jig then it is dropped into a hole in the top of the carving bench, the square wood spacer block is slipped over the screw from below the bench, and the fly is threaded onto the screw fastening the work securely to the bench.

A mahogany replacement cartouche for a c. 1770 Philadelphia clock case being carved while held to the bench with a carver’s screw.

The carver’s screw shines when creating cartouches for furniture. Mid-eighteenth century Philadelphia furniture central ornaments are carved from two inch thick blocks meant to be primarily viewed frontally. While the high relief and movement of the the design that takes advantage of the full thickness of the stock make it appear that they are sculptures in-the-round, the carving can be accomplished almost entirely with the ornament secured to the bench with a carver’s screw. The two great advantages of the use of a carver’s screw are the ability to easily and quickly loosen and tighten the fly from below to reposition the ornament as it is carved, and the fact that there is no extraneous metal in the form of clamps or fasteners on the bench to get in the way of the tools and arm movements while carving or to nick the precious sharpened edges of the carving tools.

The cartouche is being held in place on the carving bench while the block that the top frond will be carved from is glued on.

When books giving instruction in carving began to be published in the second half of the nineteenth century, the carver’s screw was universally described and illustrated as the predominate accessory for holding work. Eighteenth century work also shows evidence of the use of carver’s screws. Most of the time the threaded hole on the back of an ornament left from the carver’s screw is located where the carving finishes at near full thickness of the original blank, generally near the center of an ornament. I can’t explain the low position of the screw hole on the urn and flowers ornament on the right in the picture above.

The carving of bird ornaments also began with the blank attached to the bench with a carver’s screw though they give the appearance of being fully carved in-the -round.

Scroll moulding from the David Rittenhouse Orrery case, John Folwell and Parnell Gibbs, Philadelphia, 1771.

Carver’s screw were also used when the scrolls of curved cornice mouldings were decoratively carved.

The backs of the urn and flowers ornament and the scroll moulding on the left in the photo above both show evidence of a carver’s screw.

When the carving of the front was completed, the ornament was taken off the bench, the carver’s screw removed and the ornament was then back-cut with gouges relieving the edges of the elements carved on the face quickly and efficiently to lighten the appearance of the cartouche when viewed from the front, while maintaining thickness where necessary for strength.

This high relief bust of Bacchus attached to the door of a late nineteenth century Philadelphia walnut cabinet was carved while attached to the bench with a carver’s screw.

On the back of the bust are two threaded holes for screws that attach the bust to the door and a large threaded hole in the center left from a carver’s screw.

Carver’s screws, from left to right: mid-twentieth century Record, mid-twentieth century, unknown manufacturer, Two Cherries brand, current production.

Today at least one manufacturer produces a carver’s screw in the form it has taken since at least the middle of the nineteenth century while others produce their own modern interpretations. Eighteenth century and earlier carver’s screw would have been made from wrought iron parts supplied by a blacksmith with the threads hand filed to an individuals liking, then passed down from carver to carver until they were used up or viewed as useless or unimportant and discarded by someone who didn’t understand their use or recognize their value or importance to the history of the craft.

thanks for the excellent description of your craft!

*This really answered my problem, thank you!