The Autumn 2020 issue of the magazine Antiques & Fine Art contains the first of a series of articles I am writing to introduce the Dietrich American Foundation’s furniture collection to a broader public. The Dietrich American Foundation was founded in 1963 by H. Richard Dietrich Jr. to collect and research American decorative and fine art, primarily of the eighteenth century. A Collector’s Vision: Highlights from the Dietrich American Foundation is on view through November 15, 2020 at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The subject of this first article is included in the exhibition.

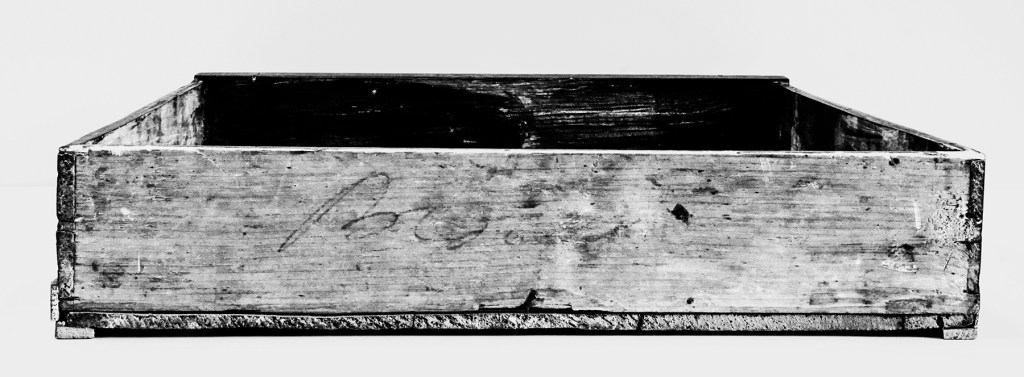

The article focuses on a single object from the Foundation’s collection, a japanned high chest, c. 1735, made by the English joiner John Brocas (d. 1740) who immigrated to Boston, Massachusetts prior to May 1696 when he is recorded as purchasing land there. Robust evidence of his furniture shop in the historical record have allowed furniture historians to study his life. But until “Brocas” was found inscribed in graphite on the exterior surface of the backs of the majority of the drawers the Foundation’s high chest, no work had been documented or attributed to him.

I believe the article to be a comprehensive overview of the object, but word count restrictions and the limited number of photographs, while completely understandable due to the needs of the magazine, meant that much fascinating and compelling information did not make it into print. There are multiple aspects of construction and design still left to explore and examine.

The idea of how joiners transitioned through changes in consumer fashions has only been touched on by furniture historians. Trained in England in the 1670s, John Brocas ended his career making cabriole leg high chests in Boston in the late 1730s. His japanned high chest can give us a small peek into how one joiner kept pace with the times.

“Ultimately, without a broad range of the early work of John Brocas to examine, we cannot know what influence he had on Boston’s furniture makers. Nevertheless, this high chest made at the end of his life represents an unusual opportunity to investigate the work of a cabinetmaker who had to navigate stylistic changes as well as technical developments in his craft to satisfy his clients, while continuing to work efficiently at his trade. We are now able to appreciate the work of this early American furniture maker whose life was known, but whose art was a mystery before this exciting discovery.”

Below is a selection of images of the high chest not published in the article.

Dietrich American Foundation

Another great post!

On Tue, Sep 15, 2020 at 10:00 AM In Proportion to the Trouble wrote:

> Christopher Storb posted: ” The Autumn 2020 issue of the magazine Antiques > & Fine Art contains the first of a series of articles I am writing to > introduce the Dietrich American Foundation’s furniture collection to a > broader public. The Dietrich American Foundation was founded i” >

Chris,

Thanks for sharing those images. I always like to see the interiors of original pieces. Seems one can learn so much from them. By the way, do the dustboards in the upper section go from front to back? It may be that I am simply looking at wear marks in the boards, but that seems to be the case on all the dustboards. If that is the case, how are they supported in the back? Great job with the images.

Frank Duff

The grain of the 1/2 inch dust boards runs side-to-side. The grooves and wear marks are from nails in the drawer bottom. The drawers originally ran on their flush bottoms, pure late 17th century technology. Wear strips were added to the drawer bottoms at a later date to alleviate the friction between the full width drawers and the dust boards. The dust boards are fit to 1/2 inch dadoes in the sides, that is their only support.

Excellent work as usual, Chris.

I find the mouldings intriguing: Despite the whole being japanned the waist mouldings are clearly crossgrain-veneered (walnut?) on a long-grain pine core.

However, the cornice mouldings are a bit of a mixed bag. The upper composite arrangement appears to be simply testudinally painted long-grain pine while the lower section is thin (long-grain?) veneer on a long-grain pine core. Is one or other a repair? They don’t look as if they were even applied contemporaneously.

Interesting thoughts about the moulding. The upper element does have a longitudinal maple veneer on a pine core. It is very difficult to see in a photo due to all of the layers of paint and varnish covering the joint, but it can be seen under magnification. (This element is replaced on the other side of the chest.) And yes, the lower section has thin long-grain maple veneer on the pine core. In the article, I discuss some of the technical workings of Brocas. The drawer fronts are veneered with plain-grain maple, the drawer sides are through-dovetailed to the fronts, just as if he were making a figured walnut-veneered chest c. 1685. This is in accord with the technique of making the moulding, same veneer thickness used on the drawer fronts and the moulding. On all other examined japanned chests made in Boston in the first half of the 18th century, the drawer fronts are solid maple and lap-dovetailed.